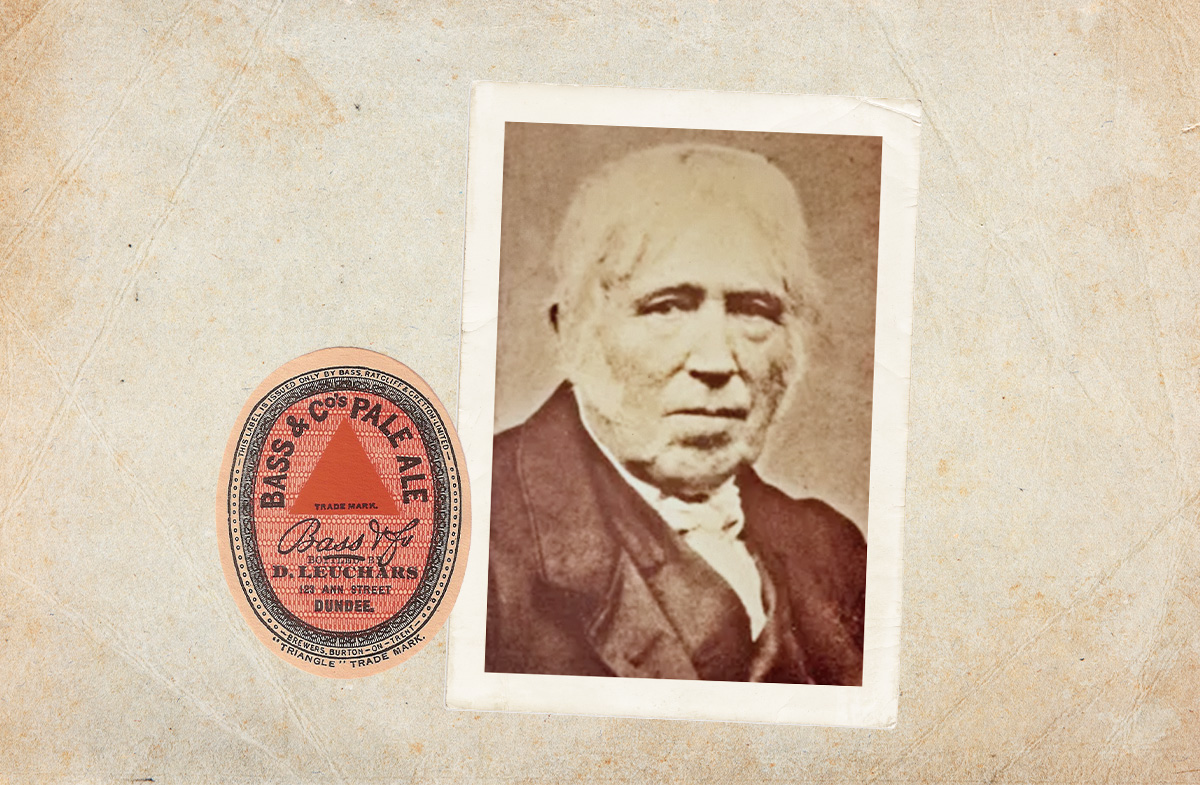

In which editor Jordan St. John goes head-to-head with an 1840s Bass Pale Ale

Over the course of my career, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about historical brewing. I wrote a book called Lost Breweries of Toronto that was nominated for a Heritage Toronto Award, and in doing so I spent a lot of time looking at archives, digitized newspapers, and fire insurance maps. It turns out that historical breweries are surprisingly flammable.

Sometimes you get very lucky. When I made Helliwell Old Ale with Muddy York, I was able to reverse engineer some detail from a well-kept diary by William Helliwell that told us how strong the beer would have been and what the process might have looked like. When I made Revelator Bock with Amsterdam, we were able to cadge ingredients from newspaper advertisements from the 1890’s (Baird Roasted Barley from Glasgow, which still exists!) and gravity readings from excise documentation in order to recreate Reinhardt Salvator.

When the Enoch Turner Schoolhouse got in touch with me to ask if I’d host a pub night for them to celebrate the 175th anniversary of the building, I suggested that we might brew a beer for the occasion.

Enoch Turner was a brewer in Toronto who lived on Taddle Creek, which also supplied mill power for the city’s first brewer in 1803. Enoch was known locally for feeding his horses beer, which the horses seemed not to mind and which people gathered round to watch. His brewery property had a small vineyard, and he was a member of the horticultural society, growing filberts and plums. He was, by all accounts, a sterling fellow.

When Toronto’s population more than doubled in 1847 as a result of the Irish famine, the neighbourhood he lived in changed dramatically and became known as Corktown. Such was the flood of immigrants that it was administratively prohibitive to write down which part of Ireland they would have been from. According to the ledger, they were from Cork.

How do you provide services for 18,000 refugees in a city that only has 15,000 citizens? The city didn’t want to pay for services as it had no tax base. The province didn’t want to pay for services as it had other problems. The 416/905 funding situation is at least 200 years old. Enoch, to his eternal credit, stepped up and funded a schoolhouse that educated the neighbourhood’s children, resulting in thousands of literate, numerate, productive members of society.

Enoch had been a pub landlord at a couple of locations in The Potteries in Staffordshire, just seven miles down the canal from Burton-on-Trent. It stands to reason that when he moved to Toronto, he would have made something like the beer he knew from just down the road in Burton. At the time, Bass Pale Ale would have been extremely widespread, and would certainly have made it as far as Toronto’s taverns by mid-century as did Guinness, Beamish, Barclay Perkins, and Allsop’s.

The difficulty in creating something approximating Enoch’s beer is that no records of his brewing survive.

All historical beer recreations are fraught with complication. Even if you had a complete ledger of brewing records, you do not have that year’s crop of barley. You do not have hops that grew in the summer of the year that beer was brewed. Guinness, which has complete records due to its longevity, still has to make assumptions for their Brewmaster’s Series; just fewer of them.

Partnering with Toronto’s Amsterdam Brewery, two of whose brewers have celebrated their weddings at the Schoolhouse, our first task was to track down the beer that would likely have influenced Enoch Turner: Could we find a recipe for Bass Pale Ale from the 1840s that would approximate the beer from the year the schoolhouse was built?

Ron Pattinson, a legendary beer historian who has written numerous books on historical brewing, immediately dissuaded us of the notion. The closest we could get was 1874.

The good news is that Bass Pale Ale is not a beer with a huge number of moving parts. It encompasses a single malt variety and a single hop variety. It’s what you’d call a SMASH beer, although it has some pronounced differences to a modern Pale Ale. It would have been 6.6% with 111 IBUs, making it just bitter enough to really frighten casual drinkers. They would have boiled for two hours, and the hard Burton water profile would have had 700 ppm Sulfate, at least according to historical records from the time.

Sulfate not only provides a crisp finish that affects the attack of hops on your palate, but it is sulfuric, giving the beer a slight extinguished matchstick quality they refer to in brewing as the Burton Snatch.

You could brew a more or less authentic 1874 Bass Pale Ale, but it wouldn’t be Enoch’s beer. He would have faced geographical limitations. For one thing, Toronto’s water has about 21.6 ppm Sulfate. It’s soft water, and that changes the way the hops would attack your palate. It would be a rounder, wider bitterness. He wouldn’t have had access to fresh East Kent Goldings, and the Ontario terroir would have changed whatever was transplanted, meaning that the hop character would have been whatever was closest.

In discussion, we decided to use Chevallier Malt from Crisp, which was tested out in Toronto in 1871 by the Aldwell Brewing Company in cooperation with George Brown, who had a hobby farm outside of Brantford. It provided about two percent more extract than the local malts of the day and is the coming thing in terms of heritage varieties. In the brewhouse it has a light note of Milk Chocolate as it hits the mash tun.

We’re using a combination of hops, including East Kent Goldings and Bramling Cross. Our thought process is that Bramling Cross contains some Canadian breeding stock with a little blackcurrant that is probably period authentic. The EKG is a combination of whole cone, since Enoch would not have had access to pellets, and pellets, since whole cone is a bit of a bear to use on the day. As we add them to the kettle, the aroma is marmalade and herbaceous hedgerow greenery.

We decided to reduce the alcohol to a slightly more sessionable strength and the bitterness from 111 IBU to a more manageable 50. After all, the people who are coming to the Pub Night might want to leave with their taste buds intact. Enoch would not have known about Burtonization. No one did until later in the century. We decided to replicate the water chemistry and the yeast from Burton mostly because it would have been what he was trying to emulate.

What will result, in just a few weeks from now, is a quintessentially Anglo-Ontarian beer that never existed, but that probably could have if everything had come together.

Enoch was influential enough that if you live in Toronto, you still feel his impact on the city daily. It’s rare that a private citizen’s philanthropic acts so profoundly echo through time that you’re able to honour his achievements 175 years later. I don’t know if it’s anything like his beer, but I like to think that if we could put a bottle in the wayback machine he’d recognize it.