The fascinating and complicated history of one of beer’s most revered figures

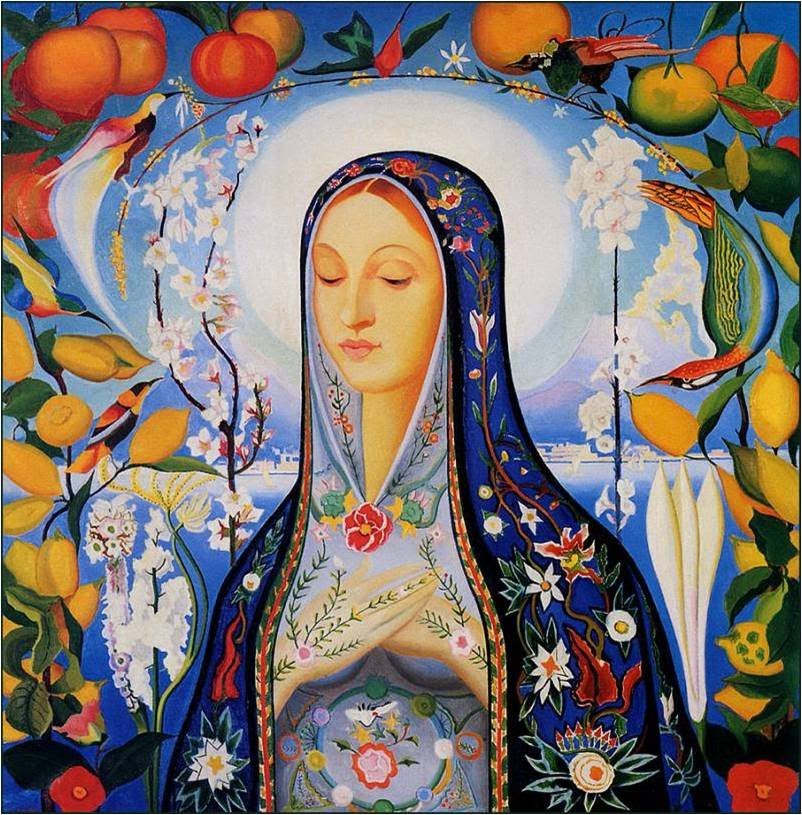

In the annals of beer history, St. Hildegard of Bingen holds a unique distinction. The 12th century German abbess is responsible for the earliest surviving writings on the use of hops in beer, and for that she has been venerated as an unofficial patron saint of beer.

“As a result of its own bitterness,” Hildegard wrote in the Physica, her classic text on health and healing, circa 1150, “[hops] stops putrification when put in [beer] and it may be added so that it lasts so much longer.”

That might not seem like much, but you have to remember, the importance of hops in beer can’t be understated. In addition to flavouring beer, hops, most importantly, kills off a lot of the microrganisms that will spoil beer, while creating an ideal environment for beer yeasts to do their thing.

The earliest proto-beers were more of a boozy porridge, likely discovered when an old loaf of bread was forgotten about in some damp corner, and wild yeasts had their way with it. Hunger will drive people to do some desperate things, like tucking into that soggy mess.

As beers came more refined, there became a greater need to preserve it, which was pretty much impossible until hops came along. It’s such an important component , the Germans even included hops in the Bavarian Purity Law of 1516, the Reinheitsgebot, which limited brewers to just four ingredients: water, malted barley, yeast, and of course, hops. (Well, technically, it was just water, barley and hops. No one had any idea what yeast was. In fact, fermentation was literally believed to be an act of God.)

In honour of Hildegard’s contribution, Driftwood Brewing recently released their Naughty Hildegard ESB. “We like Hildegard’s style and we can’t imagine beer without hops,” the beer’s label states.

However, as it turns out, her contributions to beer-making might be the least interesting thing about her.

Hildegard was born in 1098 to a noble family in the county of Sponheim, about 100km west of present-day Frankfurt. As a child she experienced visions of God, which she described as “living light.” She was given over to the care of a nun at the age of eight, who taught her to read and write, and by 14, she was a nun herself. When her mentor passed away in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously chosen to lead her Benedictine monastery.

In addition to running the monastery, Hildegard also devoted her time to writing musical compositions, poems and plays, as well as theological texts, medical books and scientific essays. She founded two monasteries, and extensively travelled around Germany on numerous speaking tours. She lived into her 80s, and she pretty much never stopped working.

Amazingly, much of that work has been preserved, and for a woman in the highly patriarchal Middle Ages, that’s unique, says University of British Columbia historian Dr. Arlene Sindelar.

“She was a woman who wrote in the 12th century and that’s not the most common thing,” she says. “She was somebody who men listened to and had significant authority, mostly in the church. They paid attention to her and she didn’t hold back when she was going to admonish somebody.”

She was a philosopher and a scientist, as well as a Christian visionary. Her most well-known work, the Scivias, details her many visions of God, and made her somewhat of a celebrity in her day.

“Any woman who makes this kind of an imprint on a culture, I think part of it is her personality, her drive, her desire to know, her desire to accomplish,” says Sindelar. “And she was supported in her fearlessness, I think, by her belief that God spoke to her truly.”

Beer, as it turns out, was never much of a priority for Hildegard, as she only ever mentioned it briefly in her writings. Her role in the development of brewing may not have been as pivotal as some make out.

Beer historian (yes, that’s a real thing) Richard Unger notes that there is evidence of hops use in beer in Northern Germany as early as the 6th century, well before Hildegard had written about it. As it turns out, Hildegard’s writings may not have even been the first to recommend the use of hops in beer, either – hers are just the oldest historians have found.

“I think her importance lies in other things than her contribution to brewing,” says Unger. “That is a very minor part of what she writes about.”

Hopped beer didn’t become popular in Southern Germany until the 15th century, he adds, so it’s clear her writings had little impact on brewing in the region.

And yet, Hildegard’s story endures. More than 800 years after she died, she’s revered as a proto-feminist icon, one of the founders of holistic medicine, a Christian mystic, as well as an important figure in brewing.

“She’s a giant among women, most of whom sink into obscurity,” says Sindelar. “But she hasn’t. She invoked the authority of God… she wrote about all these different things, from poetry to recipes to comments on health to these visions she had… and she did not hesitate to speak her mind.”

In other words, she was a total bad-ass.